Year in Program: 5

Committee Chair: Dr. Susan Sleeper-Smith

Committee Advisors: Dr. Emily Conroy-Krutz, Dr. Sean Forner, Dr. Mindy Morgan, and Dr. Michael Stamm

Fields of Interest: American History, Ethnohistory, Religion, Native American Studies, History of Memory, The Early American Republic, Settler Colonialism, Early Canadian History

Office: 317 Old Horticulture

Office Hours: Tuesday, 1:30-3:30

Education: M.A., Lehigh University (2015), B.A., Honors College at Eastern Michigan University (2013)

Email: luedtkea@msu.edu

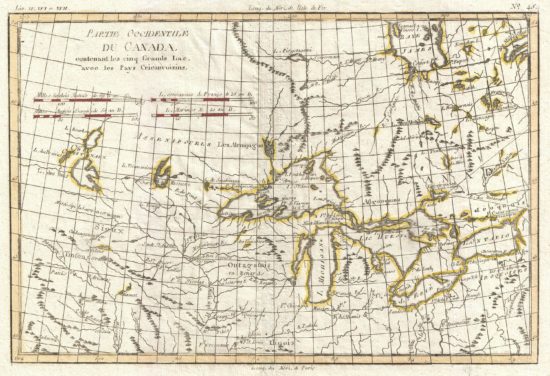

I am a cultural historian of the early United States. I am primarily focused on the intercultural relations between Indigenous groups and the various peoples of European descent that inhabited the Great Lakes region, particularly in the nineteenth century.

My dissertation entitled, “Reading Between Imperial Lines: Settler Colonialism and Indigenous Survivance in the Great Lakes Borderlands” explores the resistance strategies developed by Indigenous peoples in the wake of settler colonial tactics of Indian dispossession and removal that were enacted by both the United States and the British Empire in the first half of the nineteenth century. My research considers the Great Lakes as a holistic region throughout this era. National borders existed but mostly on paper and in the public and political imaginary, while cultural kinship networks stretched back and forth across the border in ways that repeatedly confounded imperial and state administrators. In this period, figures on either side of this border competed to assert claims of frontier exceptionalism in order to take part in the creation of early American and Canadian nationalism. My research also traces the heritage of Indigenous resistance strategies developed by Joseph and Molly Brant in the second half of the eighteenth century. Through an understanding of Euro/American concepts of land use and property value, the Brants were able to establish communities that defied settler colonial expectations and attained legal protection from the British government. Joseph Brant even managed to briefly unite numerous Indian nations throughout the Ohio Valley and Great Lakes region into a diplomatic confederacy that emulated the League of the Six Nations to deal with the land-hungry United States, especially in issues of land cessions and territorial boundaries.

My research also explores the creation of foundational myths and official historical narratives that whitewashed the violence of settler colonialism and Indigenous dispossession. Leaders like Lewis Cass, Michigan’s territorial governor and Jackson’s architect of Indian removal, and Upper Canada’s lieutenant governor, Sir Francis Bond Head, defined Native peoples in ways apropos of the public imaginary while rationalizing the dispossession and removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands. Cass and Bond Head engaged in the creation of early American and Canadian nationalism by insisting that life in the frontier provided unique experiences that directed the courses of their respective nations. However, Indigenous communities mounted resistance strategies to thwart removal and dispel the myths of their disappearance in both the United States and British Canada. Despite policies of Indian removal and reform, Indigenous space transcended geopolitical boundaries. An unenforceable U.S.-Canadian border emerged as a means of resisting imperial domination, and Indigenous migratory practices thwarted removal strategies. By the early nineteenth century settler colonialists flooded into the frontier towns of Chicago and Toronto and transformed them into significant urban spaces. During the last decades of the nineteenth century when European immigration threatened the hegemony of these growing metropolises, those in power reimagined and glorified their early nineteenth-century frontier in order to bolster their grip on political and social power. Beginning with the literature of pioneer settlers such as Juliette Kinzie and Major John Richardson, these settler societies fictionalized their interaction with Indigenous people by engaging in mythologization and collective amnesia. They created narratives that reimagined dispossession and removal as benign events, spearheaded by numerous Indigenous leaders, who they portrayed as ’Indian friends’ because they welcomed the newcomers and publicly acknowledged the demise of their own people. They transformed forced removal into the voluntary westward migration of Indians. In this context, antiquarian historians reimagined their most committed Indigenous opponents into their “good Indian” friends. Throughout the second half of the nineteenth century, Indigenous authors such as John Norton, Peter Jones, George Copway, and Simon Pokagon penned a number of counternarratives that challenged the prevailing narratives of settler colonial conquest and Indian disappearance.

My research questions have evolved because of the emergence of settler colonial theory and memory studies. At numerous workshops, symposia, and conferences I have engaged in discussions on the applicability of these social theories and ethnohistory methodologies with leading researchers from numerous disciplines. My work differs from previous scholarship because it bridges the intellectual gap between U.S. and Canadian scholarship to tell the story of a Great Lakes region that stretched from Chicago to Toronto where the border became a strategic place of Indigenous resistance. It is this new perspective that I have incorporated into my teaching, using “settler colonialism” to offer an alternate vision of history that more centrally situates historical events around the presence and persistence of Indigenous people.

I recently attended a summer workshop sponsored by NICHE (Network in Canadian History & Environment) entitled, Canadian History and Environment Summer School. This year’s theme focused on gender and the Indigenous landscape, and it explored themes of Native dislocation, depopulation, acculturation, and persistence in the wake of white encroachment in Upper Canada/Ontario. My reflection of the workshop can be read at the NICHE website.

While working on my MA at Lehigh University, I received a multi-year fellowship to research and produce a documentary film and a website that explores the evolution of the black student voice on Lehigh’s campus, especially in the midst of racial tension.

The completed film can be viewed here.

To learn more about that project, visit engineeringequality.cas2.lehigh.edu

My Masters Thesis entitled, Revolutionary Reverence: The Politics of Memory and Identity in the Baptist Church of post-Revolutionary Virginia, explores the various ways in which leaders of the Virginia Baptist Church in the early Republic, in order to legitimize their sect and appeal to the wider American public, collectively wrote their own history in a manner that emphasized their Revolutionary political heritage almost as much as it emphasized their religiosity. In doing so, these early Baptist leaders and historians memorialized the actions of their forebears in ways that placed them squarely within the political discourse of nationalism, and specifically utilized their struggle for religious freedom as evidence of a legitimate claim to America’s early national identity and heritage.

Teaching Experience:

HST 201: Historical Methods – Instructor

HST 309: Native American History – Instructor

ISS 325: War and Revolutions – Teaching Assistant

HST 202: US to 1876 – Teaching Assistant

IAH 201: US and the World – Teaching Assistant

IAH 202: Europe and the World – Teaching Assistant

HST 201: Assistant Instructor